Remembering to Sleep & Sleeping to Remember: A brief dive into Sleep and Memory

In terms of fundamental scientific inquiry, the topic of sleep is one of the most- interesting, most-expansive, and highly-studied areas of modern psychology, yet it is still a ‘blank page.’ The fundamentals of sleep may initially be perceived as being nothing more than lost time, or beyond sufficient experience or observation. Actually, though, sleep is essential to the epigenetic and biochemical functioning of all organs in the body, including cognition and memory. With the obvious psychological benefits of a good night’s sleep (optimizing concentration, mood, creativity, etc.) being well known to most of us, such trite understandings tend to overshadow the kaleidoscopically mutable psychophysiology of sleep that acts to fine-tune, reset, and even regenerate mortally-vital systems. Achieving the most-useful and most-insightful version of ourselves is always the goal, which also should involve understanding the basics of sleep and all that it entails as it relates to memory.

Sleep Basics

It’s no secret that sleep improves almost every daily function. But here’s what still seems to elude our intuition and our understanding: What is responsible for increased cognitive utility, and how is such a highly-varied orchestra of underlying mechanisms aligned and affected? For this discussion, I must include a few references that may be unfamiliar and confusing to you; so, I am defining them up front: Dual-store, multi-trace, and feed-forward modeling are all different mechanisms and pathways that are used in the brain to map and to network memory and storage centers of memory banks. They sound pretty important, don’t they? They are.

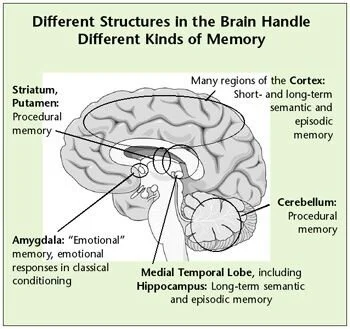

As vast amounts of information are processed and stored throughout the day in different memory centers of the brain, they seem to be more deeply entrenched, more clarified, and made meaningful only after a good night's rest. Recent research has made some headway toward pinpointing the exact biochemical to physiologic to psychological functioning that undergirds the resultant and overarching gift for these processes; revamped dual-store, distributed multi-trace, and neural-network modeling have more feasibly described the approaches to memory–from neuroscience-centered computational approaches to holistically psychological approaches (Scullin & Bliwise, 2015; Stickgold, 2005).

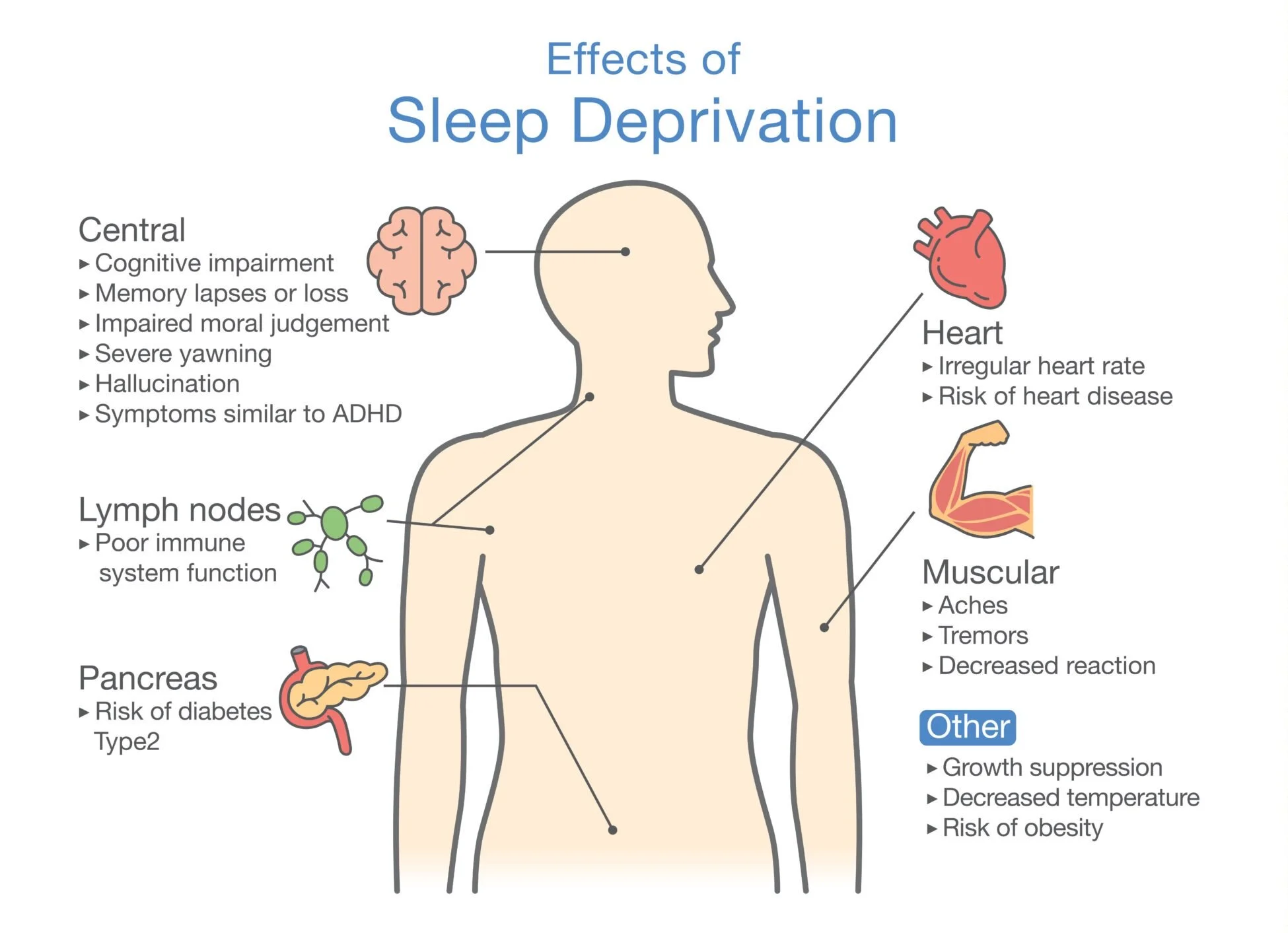

Sleep takes up approximately one-third of our lives, yet it’s more than just a blank and latent period of time that our bodies use to rest after a hectic day's work. During sleep, the body regulates and recharges key autonomic systems such as circulation, respiration, and immune response, to name just a few. Sleep also manages our daily moods and our ability to retain, recall, learn, and use the information that is stored in and plucked from our memories into our daily lives. No doubt, sleep is indeed an awesome power of the human body and the brain. Let’s consider what else might be going on inside the brain that makes sleep so special (Walker, 2009).

Different sleep stages (1, 2, 3, 4, and Rapid Eye Movement/REM) of the brain are as fundamentally important to a good night's rest as the body’s internal clock (Suprachiasmatic Nucleus) is essential to the daily rhythms (Circadian) of regulated hormonal outputs (ACTH and Leptin/Ghrelin) that prepare the body for and from sleep. In this way, these components of wakefulness and of sleep are important because they sort of oscillate—like hormones, for example—during both the day and the night. Such ebbs and flows are essential for overall good health. Likewise, one’s neurological and biochemical reactivities are dependent upon a steady balance of these rhythmic fluctuations that sort of modulate and tell the brain not only when it’s time to sleep but also, even when disrupted, when to stay asleep (Hirshkowitz et al., 2015).

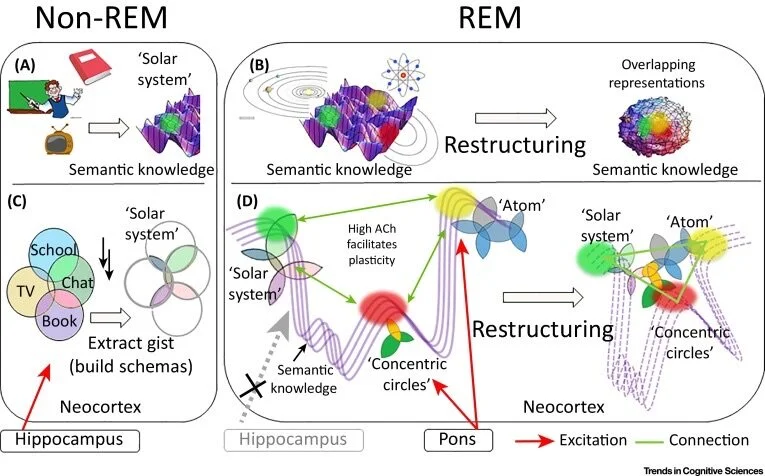

The part of sleep that is more particular to the everyday tasks of memory tends to be recalled in the early mornings when we are best at reciting these nocturnal happenings of our dreams to a loved one, to a school/work mate, or even to self through nonverbal sessions of conscious perseverance. Our dream stages of sleep are most influentially talked about and later pondered over; on a neurological to biochemical level, these exhibit corollary feed-forward reactivity that, more often than not, matches those dream stages that are evoked most readily while we’re awake (Diekelmann & Born, 2010).

However, regardless of the heightened cerebral activity of these states, we notice that these very episodes are responsible for deeper processing of daily events and tasks that were posed earlier as being cognitively abstract and problem-like. Earlier supposedly problem-like situations and scenarios are reassessed and reprocessed cognitively piece-by-piece, not just during REM but also during the slow-wave states of dreaming, into structurally cognitive representations that we readily, even involuntarily, visualize. In a solution-based manner, these dreams of memories are reconstructed and given new meaning, if not amplified altogether (Rasch & Born, 2013).

Research has long reiterated the importance of attaining a good night’s sleep. More recently, research also has focused on the benefits of REM, not only by the surmounted cognitive deterioration that is left in its absence but also by the brain's increased ability to solidify true versus false memories. It is universally well known that more sleep allows us to remember more and that the quality of sleep outweighs the number of hours we’ve slept. But, what else is involved (Stickgold & Walker, 2013)?

Sleep and Memory

Different stages of sleep govern different stages of post-encoded processing. Post-encoded processing is nearly the same as reprocessing; reprocessing is continuously happening because the mind likes to refine and clarify memories as much as possible in order to better make associations with similar thoughts and memories. This processing allows for deeper learning and solidification of information that is remembered and further stored. Research points to REM as primarily being responsible for creative and rule-based reprocessing of resolution while slow-wave sleep is suggested to account for the strengthening of declarative memory. In short, combinations of early-night (slow-wave) and later-night (Stage-2 and REM) stages of sleep are key to improving cognitive processing, learning, and recall of memories in general (Diekelmann & Born, 2010; Stickgold & Walker, 2013).

When a good night’s rest is neglected, retention rates of most learning and training tasks decrease to 50%, and progressively in more severe cases of sleep deprivation. Appropriate durations of sleep are as important as the sleep itself. Newborns require 14-17 hours of sleep. Likewise, infants require 12-15, toddlers 11-14, preschoolers 10-13, school-aged children 9-11, teenagers 8-10, young adults 7-9, and older adults require 7-8 hours of sleep. In other recent research, transitions of sleep/wake cycles have also paved the way for remodeling our current bio-psychological understandings of REM and memory. As one example, when naps present with significant durations of REM, they are suggested to equal, if not to supersede, the restful cognitive benefits that can be attained in an entire night’s sleep. Findings like these further a current hypothesis that not only centers on the importance of REM as being correlated with strict cortical memory optimizations, but also furthers the idea that strictly unique phasic stages of REM are specifically important to post-learned encoding, reprocessing, and consolidation of memory (Hirshkowitz et al., 2015; Rasch & Born, 2013; Scullin & Bliwise, 2015).

Summary

Sleep is everything! It touches every fiber of our being. To best allow your brain to intellectually ferment and to optimize the positive biological and psychological underpinnings of your memory, aim to attain a full night of uninterrupted sleep. While the benefits of sleep seem to be only surface deep, they are in fact integral to the body’s performance; they are reciprocated systemically to bolster our psychological health and our overall well-being. Remember to encourage all in your household to get a good night’s sleep!

© 2022 Christopher Schroeder of New World Psychology, LLC.

Past Comments:

“Sleep is so important and this laid out even more reasons on why it’s so important. Now the trick is, how do you get enough (quality) sleep with the stressors of today?”

—Jillian S. (April 2022)

“Some great insight. I’m passing this along to my colleagues and parent friends ASAP. Thanks Chris!”

—Connor P. (July 2022)